[ad_1]

The story so far: Amping up pressure on Niger’s mutinous military junta on Saturday, July 29, the African Union demanded the country’s military “return to their barracks and restore constitutional authority” within 15 days. The European Union also announced the suspension of security and funding cooperation with Niger, declaring that the 27-country bloc would not recognise the putschists who have confined the democratically elected President Mohamed Bazoum to his official residence since Wednesday.

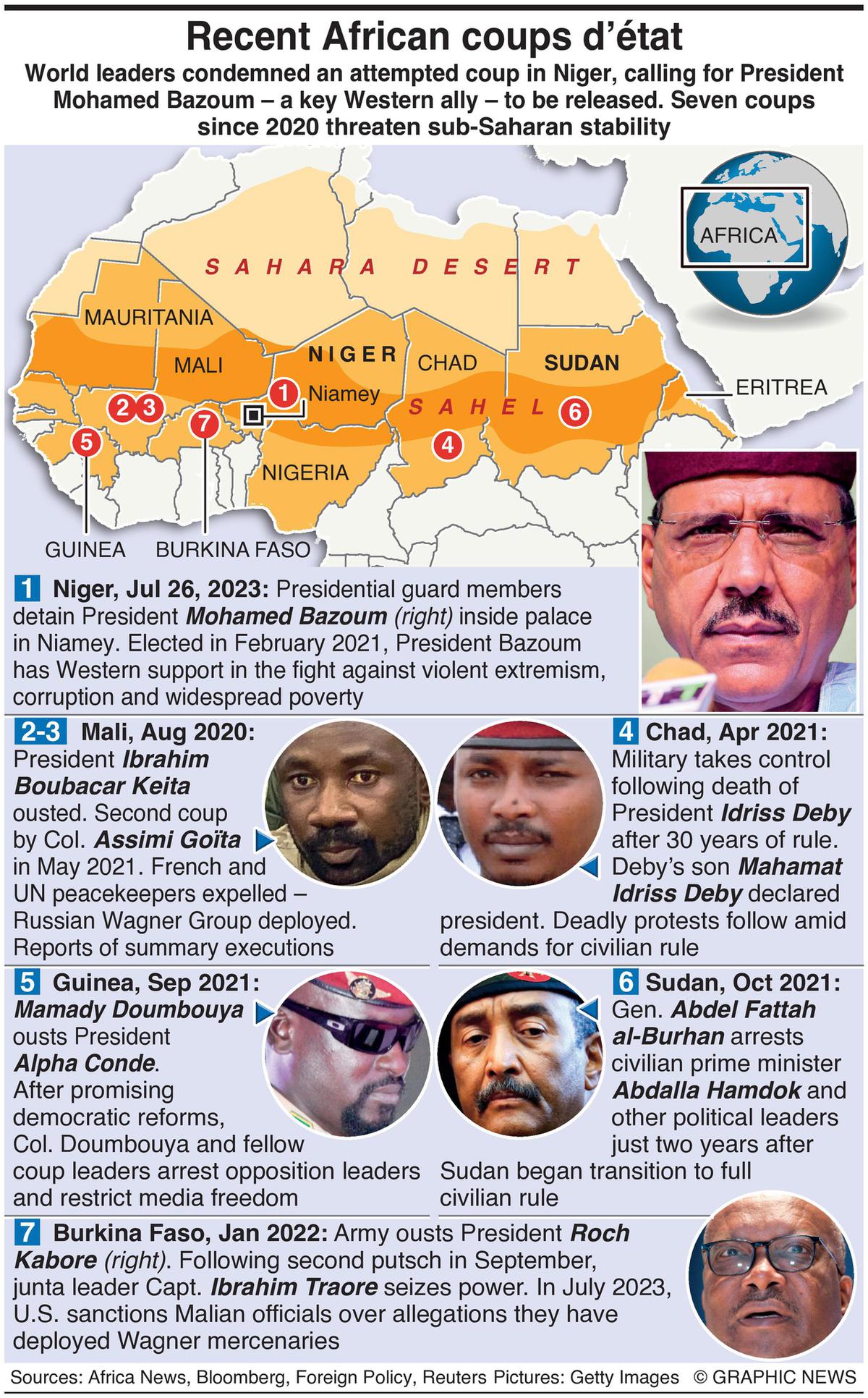

On Friday, leader of the coup General Abdourahamane Tchiani, the Presidential Guard since 2011, appeared on state television to declare himself the new leader of the troubled West African country. This is the seventh coup in western and central Africa since 2020, including two each witnessed by Niger’s neighbours Burkina Faso and Mali.

A snapshot of Niger’s political history

Niger is a vast, arid country in West Africa, twice the size of France. Having a population of about 25 million, the largely-agrarian country is one of the poorest in the world and has ranked low on the Human Development Index over the decades, vulnerable to the extreme weather effects of climate change which threatens food security. Niger, however, also has gold mining reserves and 5-7% of the global production of uranium.

Also read: Explained: The coups in West Africa and the regional response

It was a French colony until 1960, like many of its neighbours. It faced a long period of instability post-independence and was rocked by four military coups between 1974 and 2010. Like other countries in the wider Sahel region, the African region separating the Sahara Desert in the north from the tropics to the south, Niger has also faced the rise of Islamist extremist groups, armed local militias supported by stretched state security forces to counter the jihadist threat, and the resulting violence and displacement.

Mahamadou Issoufou came to power in 2011, winning legislative elections. Under his two-term presidental rule, Niger saw a semblance of political stability. In 2021, when Mr. Issoufou agreed to step down after completing his second term, the maximum number of successive terms allowed to a leader, his Cabinet Minister Mr. Bazoum was elected President, in the first democratic transfer of power since the country’s independence.

What is happening now?

On Wednesday, July 26, the President, Mr. Bazoum, and his family were detained by elite troops in Niger, who declared that they now held power. While the President, who has not resigned, has since been confined to his official residence by the military, a group of soldiers appeared on national TV on Thursday, declaring that they had overthrown Niger’s government. Colonel-Major Amadou Abdramane said “all institutions” in the country would be suspended, borders closed and a curfew imposed.

He explained the rationale behind the military takeover, citing a “continued deterioration of the security situation” and “poor economic and social governance.” Armed forces chief General Abdou Sidikou Issa threw his weight behind the putschists saying it was “to avoid a deadly confrontation.”

Putting prevailing confusion to rest, General Tchiani said in a television address on Friday that the nation would now be run by a newly formed military body, the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland (CNSP). “The President of the CNSP is the head of state,” an officer said, reading out a statement. General Tchiani presented the coup as a response to “the degradation of the security situation” linked to jihadist bloodshed.

Also Read: Coup in Niger: On the ouster of President Mohamed Bazoum

Meanwhile, Mr. Bazaoum has not made a statement since Thursday morning, when he vowed to protect “hard-won” democratic gains in a post on social media. Western allies and international organisations have stood by Mr. Bazoum, saying that they did not recognise the coup-plotters as the leaders of Niger.

Does the coup bid follow a pattern in the wider Sahel region?

The Sahel region is made up of six Francophone countries—Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Senegal,— collectively home to more than one hundred million people. After independence from the French, these countries have faced long periods of political instability, economic and ethnic strife, violence over control of natural resources and the adverse impacts of climate change.

The multifold issues of weak governments, often composed of elites of certain ethnic communities, engaging frequently in corruption and unable to register economic and social progress, led to military takeovers of elected regimes under the pretext of restoring stability. Ethnic clashes and rebellions led stretched militaries to support local civilian militias to counter conflict, which in turn led to widespread violence and human rights violations.

A report in the BBC quoted research by Central Florida and Kentucky Universities to state that coup attempts in Africa “remained remarkably consistent at an average of around four a year between 1960 and 2000.” While the number of coup d’états in the larger African continent and the Sahel were high till the turn of the millennium, a decline was witnessed in the 2000s, followed by an upswing since 2020.

Also read: Terror in the Sahel: On growing Islamist violence in Africa

A renewed chapter of instability began in in 2012 when the then fairly dormant rebellion of the Tuareg people, which had taken place in the 1960s, 1990, and 2006 in northern Mali, resurfaced and spilled beyond the country’s borders. The crisis was compounded by the collapse of the Muammar Gaddafi regime in bordering Libya, which caused an influx of extremists and arms into the Sahel.The rebel groups, who demand a separate state for the Tuaregs— a mere 10% of the Malian population—organised and aligned themselves with multiple Islamist groups, including al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). This led to violent Islamist groups gaining ground in the tri-border region between Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso, controlling territory and conducting attacks.

Former colonial actor France stepped in with military support for local armed forces in the Sahel to prevent the resurgence of non-state armed groups across the region. Around 4,500 French personnel were deployed with the local joint counter-terrorism force. First, a French-led Operation, titled Operation Serval, started in 2013, targeting Islamic extremists linked to al-Qaeda who took control of northern Mali. However, in 2014, the mission was scaled up, renamed Operation Barkhane, and aimed at countering terrorism in the wider region.

While Operation Serval was seen as fairly successful, as France regained Mali’s northern regions from the extremists in 2014, Barkhane saw the growth of new groups affiliated to terrorist organisations, including the Islamic State.The period also saw widespread human rights violations by security forces and increased recruiting to fight the crisis.

The situation also resulted in several military takeovers, justified by the militaryciting the inability of civilian governments to ensure economic stability and national security against extremists. The coup plotters also capitalised on the anti-French sentiment in sections of the populace, and gained some popular support for ousting leaders seen as pro-Western.

Have military takeovers lessened the violence in the Sahel?

There’s no concrete evidence that military takeovers restore stability and bring down violence. The crisis monitoring group, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), points out that successive military coups in the recent past have caused regional instability and the weakening of state institutions. It recorded that in 2022, the number of reported deaths from political violence increased by 77% in Burkina Faso and 150% in Mali from 2021.

The Africa Centre for Strategic Studies (ACSS) points out that some coups have become a means of grabbing power by politicised security elites on the pretext of restoring security and order. “Many of these recent military coups have been led by colonels commanding presidential guards or special forces units rather than military leaders at the top of the chain of command,” it notes. “These elite units are often provided specialised training, equipment, and salaries to enhance their capacity. Over time, some of these units have become politicised and accustomed to their privileged space near the centre of power.”

This trend is evident in the fact that even though Niger was seen as managing insurgencies and extremism better than its neighbours Mali and Burkina Faso, the Nigerien putschists also cited the worsening security situation as a reason for their uprising.

In fact, the ACSS states that under the last decade of democratically elected regimes in Niger, the country saw economic progress and an increase in public accountability. The United Kingdom think tank Chatham House also points out that Niger became a better example in the region when it came to improving ethnic inclusivity in governance and dealing with insurgents.

Why is the West concerned about NIger’s coup affecting security in the Sahel?

Niger, owing to its relative stability, had become a democratic outlier in the Sahel following military takeovers in neighbouring Mali, Burkina Faso and Chad since 2020. After military coups and anti-French sentiment, France’s relations with the military rulers grew hostile in Mali and Burkina Faso. Mali last year expelled the French ambassador when he disagreed with the junta’s decision to remain in power until 2025, and Burkina Faso’s military government also announced its decision to end its military agreement with France and called on Paris to withdraw its troops within a month. France shifted more than 1,000 personnel to Niger after withdrawing from Mali last year. In such a situation, the landlocked Niger was viewed by analysts as the West’s “only hope” in the region to fight the militants.

The country also played an outsized role in America’s Africa strategy and became a key partner for Washington’s fight against Islamist insurgents, who have killed thousands of people and displaced millions more. U.S. military personnel have been training local forces to fight militant groups.

Western countries poured resources into Niger to bolster its security forces in the face of a growing insurgency linked to al-Qaeda and Islamic State. The U.S. says it has invested about $500 million since 2012 to help Niger boost its security. There are some 1,100 U.S. troops in Niger, where the U.S. military operates out of two bases. In 2017, the government of Niger approved the use of armed American drones to target militants.

Between 1,000 and 1,500 French troops are based in the country, with support from drones and warplanes. Their role is solely to support the Nigerien army when it identifies insurgent activity in the border regions connecting Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. The European Union also decided last year to set up a three-year military training mission in Niger, to which Germany contributes troops. Italy also has about 300 soldiers in the country.

Now, with Niger also falling into the hands of a military-led leadership, it is unclear whether the U.S and European countries would be able to impact security in the Sahel region through Niger. The U.S. has supported the ousted leader Mr. Bazoum, and said that a military takeover may cause it to “cease security and other cooperation with the government of Niger, jeopardizing existing security and non-security partnerships.”

How does Russia figure in the crisis?

Multiple pro-coup protestors in Niger this week were seen waving Russian flags in the protests outside the National Assembly, the country’s legislature. Notably, the anti-French sentiment in the Sahel has been seen as a reason for Russia making inroads into the region. Mercenaries from Russia’s private military Group Wagner are already active in Mali, from where the French have withdrawn troops after a decade. The country also asked the United Nations to withdraw its MINUSMA peacekeeping mission.

Burkina Faso is reportedly involved with the Wagner group to deal with surging jihadist violence. After officially announcing the end of the French operation in November 2022, Burkina Faso turned towards Moscow taking steps similar to Mali.

Incidentally, Wagner chief Yevgeny Prigozhin expressed his support for the putschist takeover of Niger. “What happened in Niger is the fight of its people against the colonizers. … It effectively means winning independence. The rest will depend on the people of Niger,” he said in a statement on Thursday.

Observers now fear that Niger will also open its doors to Russian influence through Wagner. Besides, Russia has also been accused by the West, particularly France, of spreading disinformation in Africa; France said last month that it found Russian-linked disinformation campaigns in the region targeting the French government.

[ad_2]